- Home

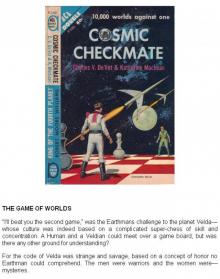

- Cosmic Checkmate

Charles DeVett & Katherine MacLean Page 5

Charles DeVett & Katherine MacLean Read online

Page 5

“Are you from Earth?”

“No. My home world is Mandel’s Planet, in the Thumb group.”

She indicated a low hassock of a pair, and I seated myself on the lower and leaned an elbow on the higher, beginning to smile. It would have been difficult not to smile in the presence of anyone so contented. “How did you meet Trobt?” I asked.

“It’s a simple love story. Kalin visited Mandel,—without revealing his true identity, of course—met, and courted me. I learned to love him, and agreed to come to his world as his wife.”

“Did you know that he wasn’t, . . That he …” I stumbled over’ just how to phrase the question. And wondered if I should have started it.

Her teeth showed white and even as she smiled. She propped a pillow under one plump pretty arm and finished my sentence for me. “… that he wasn’t Human?” I was grateful for the way she put me at ease—almost as though we had been old friends.

I nodded.

“I didn’t know.” For a moment she seemed to draw back into her thoughts, as though searching for something she had almost forgotten. “He couldn’t tell me. It was a secret he had to keep. When I arrived here and learned that his planet wasn’t a charted world, was not even Human, I was a little uncertain and lonesome. But not frightened. I knew Kalin would never let me be hurt. Evert my lonesomeness left quickly. Kalin and I love each other very deeply. I couldn’t be more happy than I am now.”

She seemed to see I did not consider that my question had been answered—completely. “You’re wondering still if I mind that he isn’t Human, aren’t you?” she asked. “Why should I? After all, what does it mean to be ‘Human? It is only a word that differentiates one group of people from another. I seldom ‘think of the Veldians as being different— and certainly never that they’re beneath me.”

“Does it bother you—if you’ll pardon this curiosity of mine—that you will never bear Kalin’s children?”

“The child you saw the first morning is my son,” she answered complacently.

“But that’s impossible,” I blurted.

“Is it?” she asked. “You saw the proof.”

“I’m no expert at that sort of thing,” I said slowly, “but I’ve always understood that the possibility of two separate species producing offspring was a million to one.”

“Greater than that, probably,” she agreed. “But whatever the odds, sooner or later the number is bound to come up. This was it.”

I shook my head, but there was no arguing a fact. “Wasn’t it a bit unusual that Kalin didn’t marry a Veldian woman?” “He has married—two of them,” she answered. “I’m his third wife.” I realized suddenly that her warmth was as much because she was homesick, and that she longed to see and speak with someone from the Ten Thousand Worlds, as it was interest.

“Then they do practice polygamy,” I said. “Are you content with such a marriage?”

“Oh yes,” she answered. “You see, besides being very much loved, I occupy a rather enviable position here—I, ah—” She grew slightly flustered. “Well—the other women— the Veldian women—can bear children only once every eight years, and during the other seven . . She hesitated again and I saw a tinge of red creep into her cheeks. She was obviously embarrassed, but she laughed and resolutely went on.

“During the other seven, they lose their feminine appearance, and don’t think of themselves as women. While I—” I watched with amusement as her color deepened and her glance dropped. “I am always of the same sex, as you might say, always a woman. My husband is the envy of all his friends.”

After her first reticence she talked freely, and I learned then the answer to the riddle of the boy-girls of Velda. And at least one reason for their great affection for children.

One year of fertility in eight…

Once again I saw the imprint of the voracious dleeth on this people’s culture. In their age-old struggle with their cold planet and its short growing seasons—and more particularly with the dleeth—the Veldian women had been shaped by evolution to better fit their environment. The women’s strength could not be spared for frequent childbearing—childbearing had been limited. Further, one small child could be carried in the frequent flights from the dleeth, but not more than one. Nature had done its best to cope with the problem. In the off seven years she tightened the women’s flesh, atrophying glands and organs—making them nonfunctional—and changing their bodies to be more fit to labor and survive—and to fight, if necessary. It was an excellent adaptation—for a time and environment where a low birth rate was an asset to survival.

But this adaptation had left only a narrow margin for race perpetuation. Each woman could bear only four children in her lifetime. That, I realized as we talked, was the reason why the Veldians had not colonized other planets, even though they had space flight—and why they probably never would, without a drastic change in their biological make-up. That left so little ground for a quarrel between them and the Federation. Yet here we were, poised to spring into a death struggle.

And what of the Veldians today, I wondered. That early survival asset was no longer necessary, now that the dleeth had been all but eliminated. It could only be a drag on the culture—and a social tinder pot.

“You are a very unusual woman.” My attention returned to Trobt’s spouse. “In a very unusual situation.”

“Thank you,” she accepted it as a compliment. She made ready to rise. “I hope you enjoy your visit here. And that I may see you again before you return to Earth.”

I saw then that she did not know of my peculiar position in her home. I wondered if‘she kenw even of the threat of war between us and her adopted people. I decided not, or she

would surely have spoken of it. Either Trobt had deliberately avoided telling her, perhaps to spare her the pain it would have caused, or she had noted that the topic of my presence was disturbing to him and had tactfully refrained from inquiring. For just a moment I wondered if I should explain everything to her, and have her use the influence she must have with Trobt. I dismissed the idea as unworthy—and useless.

“Good night,” I said.

VI

I never did ask Trobt for details of the Final Game. There would be little point. No matter how much one knew about it, in the end he would die. I preferred to let it come as something unknown.

Conversely, I never discouraged Trobt from talking about it. I would show as little timidity as possible. Once he spoke of it at some length while we walked in his gardens.

“The near prospeot of entering the Final Game, I would imagine, must heighten a man’s awareness of all about him,” he said. “I do not know if he would see things more clearly, or whether he would merely see them in a different light. Perhaps a bit of both. Certainly everything he observed would be colored by it.”

He waited for no comment from me. “It would be a time for a man to sum up his philosophy, to review his life, and decide which of his past conduct had been right and which v wrong. That last would be difficult. I suppose the most he could ask was that he had followed his philosophy to the best of his ability—even though he might never have put it into words.

“Then there is the decision of how he will meet his final test. Will he give it his best—knowing that the best can have only the same inevitable result? Or will he decide to lose early? To avoid the trial and pain, and end the suspense before his last reserve of moral stamina is gone, and he is left a coward in the eyes of his fellow men who watch?

“Strangely enough, something about you,” Trobt continued, “has aroused an empathy in me which I have never felt before, even when former friends faced the tests.” He mused, almost to himself, “Perhaps I should guard against that feeling. I’m convinced by now that you are a man whom other men instinctively like. My allowing it to affect me could very well hinder me in the task I must perform.”

He coughed and went on briskly. “I have always felt that a man, to prove himself a man, must give the last iota of his ski

ll and strength in the Final Game. That the man who quit before he had to was a craven. Now I see it differently, and I am not so certain. Perhaps the man I considered a coward had seen the test in the new light I mentioned; perhaps he had a new wisdom; perhaps he then saw something that I did not see.

“I do know that I have never pitied a man so much as I have those who fought the hardest. Who fought up to and beyond their strength—until they broke. Then they had nothing left with which to hold up their pride. Some stood and cried—strong men, I knew—some ran, and others begged to be spared. I was sick with the humiliation I saw in them.” I did not need to hear this from Trobt to make my choice. I had already decided that I would give the best I had in the Final Game, but that above all else, I would die like a man. They would never see me crawl or beg. This was an innate determination, above and apart from any consideration of how my behavior would reflect on the Human race. It was something that had to be done. For the first time then I had a clear understanding of Trobt’s ‘yag hogt’n’balt’. I must fight.

But also I recognized fear. Fear of the breaking of spirit he had mentioned. Back on Earth I had had a very dear friend who had died of the me form of cancer that science had never been able to conquer. My friend was as brave a man as I have ever known. When he learned that he had contracted the fatal disease he had not complained. He faced the coming end without flinching, and bore its steadily increasing pain certainly better than I knew I could have done. But as the final crisis grew nearer, as the continual, agonizing torture persisted and increased, as his mind grew less coherent, I watched his distress teat something out of his spirit. The hard core of courage which he had possessed before was gone, and he had nothing left with which to fight. He was not the same man he had been before. What he had been was no longer there. When they touched him then to move him he screamed for them to be gentle. He would not eat because of the pain. Between spasms of agony—that drugs could no longer hold back—tears of self-pity would flow from his eyes, and he would beg us, his impotent friends, to help him. The place that Trobt had touched was still raw from the memory of him. Could I hope to be any stronger?

“I doubt whether one is doing a man a kindness to warn him in advance of the time of his Final Game,” Trobt broke into my introspection. “Perhaps it is better to wait until the last minute. I do not know. I suppose it depends on the man.” I recognized only then that he had been speaking Earthian. For a moment I wondered why. Then a second thought came. The whole tenor of his talk had held some overtone of sadness. Was he trying to tell me something? Or ask me something. Could he mean … ?

I turned sharply to face him. Perhaps he read fright in my eyes; I know there must have been at least apprehension there. For I saw the pity in his eyes as he nodded.

“It begins tomorrow,” he said.

VII

The night after Trobt informed me I was to undergo the Final Game I slept only the last few hours before dawn. The first hours after retiring I spent recording the events of the day on the nerve tape. I had difficulty restraining myself from recording reactions that were merely the result of my own emotional over-charge. And that I wanted very much not to do.

Because—I was ashamed to admit it, even to myself—I was morbidly afraid. The certainty that I would die before the Final Game was completed was more than I could face with steady nerves.

And yet my fear was a purely physical reaction. My mind was, if not unafraid, calm. Mentally I was satisfied that my life had been a good one. It had been stimulating, with perhaps more peaks of pleasure and enjoyment than the average man experienced. If I died now I could not feel cheated. I was very nearly content. But my body …

My body persisted in exuding a cold perspiration that made it cling to the bed covering as I turned restlessly. My bowels forced me to make frequent trips to the lavatory, and each time I rose I detected a faint odor of fear that made me want to retch in self-disgust.

I knew that only the stupid man has no fear, yet I violently resented the inability of my mind to maintain its control over my body and its functioning. I no longer felt one with it, and watched it as would a stranger who stood at my side. When I moved, it was as if I were operating a machine with rigid mechanical controls. And as the night wore on the numbness in my body washed up a wave of black despair into my brain. When I was able to think at all coherently it was with a desperate effort to find a way to escape the ordeal before me.

Father, if it be …

The next morning my bodily misbehavior was gone, but it was replaced by a frigidity of emotional response to everything around me. I felt drained of sensation, and dry, like old paper that crumbles at a touch.

As I met Trobt and we walked toward the tricar tunnel, I noted without caring the three guardsmen who fell into step with us. On the active level of my mind I was thinking of—nothing. The annotator in the comer of my skull alone was observing everything about me. But then it always did.

It watched and made note of every speech and action of Trobt and the guardsmen, their reactions to me, whether favorable, unfavorable, embarrassed, uneasy, or whether concealed or unreadable. Likewise it set down any reaction of one to the other, briefly marking smiles, gestures, and significant voice tones.

Yet I felt and showed no reaction to anything I observed. Even to myself I never specified any response to the words and expressions of those beside me, merely let them silently take their place in the memory banks of my annotator.

“Pardon.” Trobt’s words broke into my mental paralysis. “I’ve forgotten my side piece.” He smiled stiffly. “It’s a weakness of vanity perhaps,” he said, “but I am undressed without it.” He turned and retraced his steps.

As we waited a guard flexed his shoulder irritably and pulled at an arm strap. He spoke something to a second guard that I couldn’t hear. The other helped him make an adjustment on the strap. The third guard watched idly. For just an instant all three were turned away from me—and the time had come!

I had not known that I intended to escape until I made my move. Only then I understood that the annotator had been waiting until all data was in before making its decision. With that kind of mind the last possible moment is the right time to solve precisely the situation as it presents itself, and not be hampered by earlier decisions fitted to a half understanding of the upcoming arrangement of the game.

The opening into a side hall was only a few feet from my side. I stepped quickly around its comer. To the spring door of a disposal chute.

Holding the door back with my shoulders I kicked once and I was inside, and sliding down a surface made slick by the juices of discarded refuse.

For an instant a small doubt irked at my mind. Had the escape been too easy? Something like the single opening I had left Trobt in the first Game? If the man learned as rapidly and efficiently as I had seen him do in small tilings … Was he still playing the Game with me? I decided against it. Very likely the thought that I might try to escape and take refuge in the City hadn’t occurred to him. And if I were wrong, and he had planned this—for a purpose I could not see—I might turn my freedom to my own advantage. And finally, what did I have to lose?

I could not stop my descent but after a few experiments I found that I could slow it by pressing my hands and knees against the side of the chute. Despite this I hit the water with force enough to carry me under.

I came up into almost complete darkness. The odor around me was foul, and unsavory chunks of garbage bumped against my face and body.

I made no effort to swim, merely keeping my head above water and letting the current carry me along. I rounded a bend and ahead I could see the dim light of an opening. With slow easy strokes I guided myself toward it.

I stayed under Hearth City for two days. At first I had intended to go out through the breach in the wall that served as an exit for the river that flowed beneath its ramparts—River Widd, it was called—but decided against it. Out in the open they could easily run me down, while this made a pe

rfect hiding place. I fully expected them to send men to hunt for me, but I saw readily that it would be an almost impossible task to find me. Most of the vast underground was in darkness and its innumerable foundations, pillars, mud flats, and disposal exits would require an army to explore adequately.

The first several hours of freedom I took the risk of shedding my heavy cloak and clothing and spreading them in the sun that came in through the gap in the wall. When they were passably dry I put them on again and crawled back into the darkness. I found a semi-dry spot high on a mud bank, and waited. My heavy cloak held off most of the cold. I was not too uncomfortable.

There was no sign of pursuit during the morning and twice I napped. Late in the day the sound of dripping water, perhaps fifty yards to my right, reminded me that I was thirsty. I crawled to the spot from which the sound came and found a leak in a pipe that brought fresh water into the city. I caught the dripping water in my hands and drank my fill.

For all of the two days and nights tinder the city I stayed near the leaking pipe, and water was my only sustenance. The nights were miserably cold and even my cloak could not keep me warm. Each morning I crawled back to the sunny spot and allowed the warmth to creep back into my flesh.

By the second morning I knew I could wait no longer. I had to have food, and a better place to sleep. I had explored the part of the underground made visible by the light from the gap and found a stairway leading up to the city. They might be expecting me at the top, but it was a chance I had to take.

No one waited for me as I came out of the passageway. The hardest part was over.

My chances of remaining free should not be too bad, I decided. I looked enough like the Veldians to pass readily as one of them, and securing my needs would not be difficult.

I stopped at a street stall a short distance from the ramp exit with just the semblance of a plan in mind. One of the reasons I had stayed the two days underground was to give my beard time to grow. It was tough and dark and the two days had brought a short but thick stubble. It was a bit skimpy as a beard, but if I could get by a few days more it would serve.

Charles DeVett & Katherine MacLean

Charles DeVett & Katherine MacLean